This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

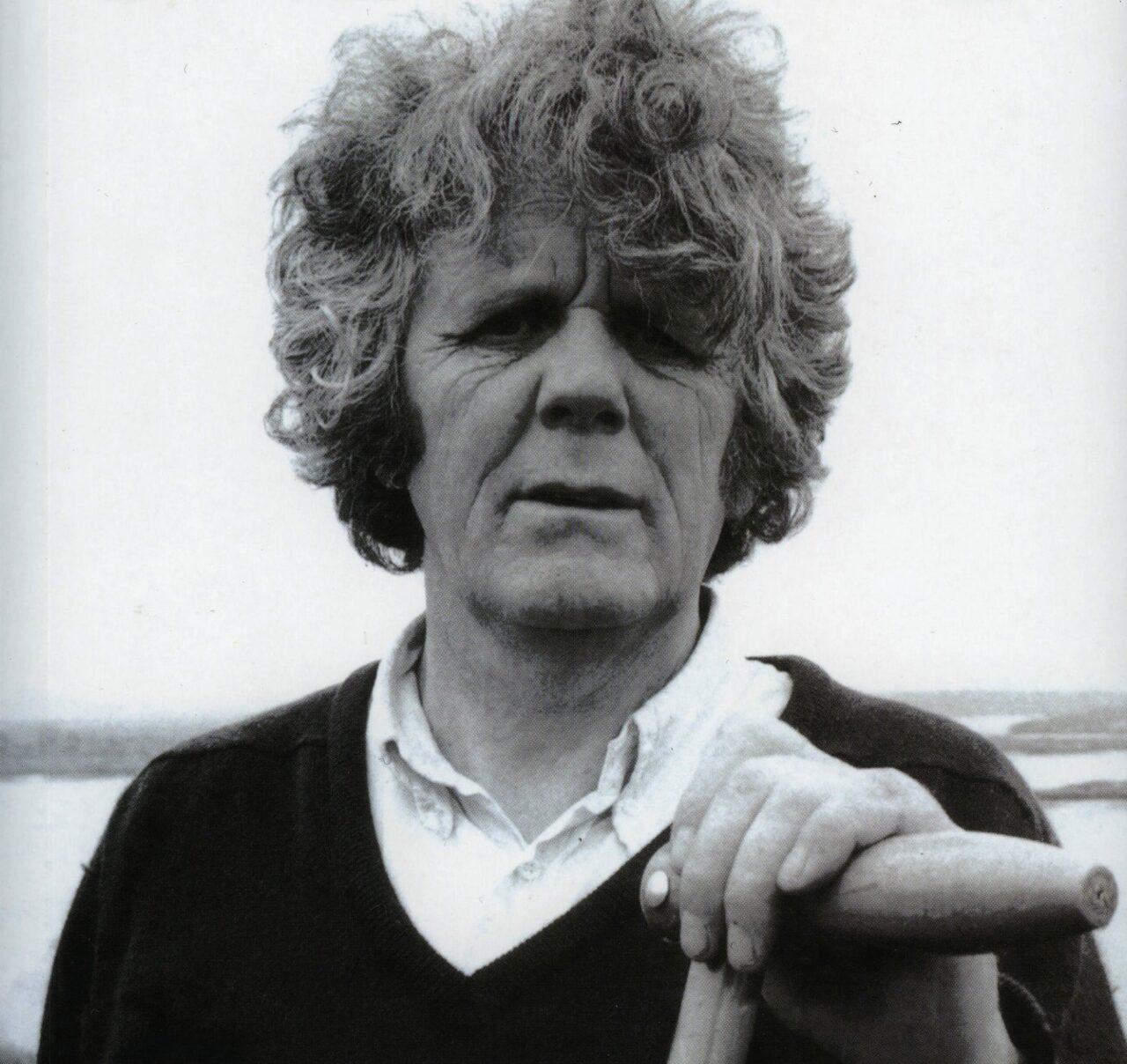

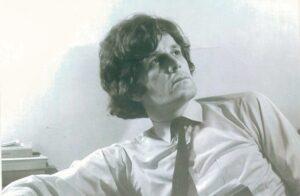

Part 2 of the Irlandnews series on John Moriarty

:: Zur deutschen Übersetzung: KlicK

:: Part 1 in English can be found here: click

On the afternoon of last New Year’s Eve I felt restless and the need to complete a long awaited task in the vanishing year: To find the place where John Moriarty wanted to found the monastic hedge school Slí na Fírinne, a retreat place in the mountains between Kilgarvan and Gougane Barra. I had been travelling the townland of Cummeen Upper more than two years ago – only now, on the last day of 2023, was I to find the 23-acre piece of land in the lonely mountains of Kerry close to the West Cork border.

John Moriarty had bought a piece of land here two decades ago with the help of sponsors. At dusk, I met farmer Patsy Randles at the end of boreen in a remote upper valley. Would he know the plot of land that John Moriarty once bought?

Patsy knew it. His sheep still graze there. He well remembered John Moriarty’s plan 20 years ago to build a retreat centre for twelve residents and guests in the seclusion of Cummeen Upper, in order to initiate the renewal of Christianity and a project to save life on earth: Slí na Fírinne, the Way of Truth.

Patsy offered me a ride on his quad bike. We glided down through the Clover Field and soon reached an adjoining large level field. This is where the monastic nucleus for the renewal of human existence, a small settlement in the shape of a blossom, should have been built.

As usual, Patsy was travelling without his phone. He had left it at home and simply didn’t want to deal with it. The sheep farmer wondered about people who were attracted and addicted to these small devices. He preferred to look at the land and his animals. He had observed young people who even took photos of their cup of tea with their smartphones but no longer knew how tea was made. “They use one tea bag per cup and no longer know how to use a teapot.” John Moriarty would certainly have liked to have had a chat with Patsy.

John recognised many deep truths in the lives of common country people. He could talk for an hour and more about a little encounter with a farmer and the extraordinary he had discovered with keen perception in the ordinary and the everyday. John had practised for a long time to clear his perception from thought patterns, preconceptions, prejudices and concepts and to see the world from a pure, unbiased perspective. He didn’t do all of this by choice, rather it had happened to him since he had a number of drastic experiences as a young man growing up.

. . . that God had created the world 4004 years before the birth of Christ

John had a traditional Catholic upbringing in rural Kerry. At school he learnt that God had created the world 4004 years before the birth of Christ. He felt, as he would later say, at home, safe and secure in this great story. At the age of 17, a book found its way to him that would turn his life upside down: Charles Darwin’s work on the evolution of life, The Origin of Species, which was banned in Ireland at the time. After reading the book, everything changed: young John had fallen out of his story and became inwardly distraught and felt shipwrecked. He had lost his sheltering God and was to spend decades travelling in search of him.

These were inner journeys into the depths of the unconscious, into the mythological time before historical time, to the very bottom of the Grand Canyon, to the beginning of life on earth. To do this, he had to leave behind his life and career as an up-and-coming academic in Canada. At the age of 33, he ended his career as a young professor of European Ideas at the University of Manitoba and retreated to the wild nature of Ireland’s west for over 20 years.

Young Moriarty felt a great urge to rid himself of the cultural conditioning and the imprint of his Western education. Back in Ireland, he experienced a mystical initiation in a bog in Connemara: Having startled a hare he collapsed into the hollow form of her nest. He could still feel the warmth of the hare and perceived its smell. Crouching on the ground, he asked the hare’s form to heal his European head, to suck all European culture and education out of it. For he knew deep inside that this European perception would continue to do no good either for the world or for himself.

On the way home, Moriarty felt the need to baptise himself. He dipped his head three times under water in a stream. He later described this ritual with the words: “I baptised myself out of culture and out of Christianity.” From then on, he forbade any boundaries to his thinking and avoided all limitations imposed by others. He moved inwardly and physically freely and unprotected in dangerous territory.

In 1990, Moriarty explained to an RTÉ television reporter why he had to go in search of his bush soul, why he had to shed his cultural imprint, de-civilise himself and retreat into nature and seclusion. He showed her a young rhododendron plant that he had grown in a pot and told her:

“After a year, the roots of the plant hit the dead plastic of the pot. They can’t get through. They wind their way back into the old soil, which they have already exhausted themselves. The plant pot.bound. It should now be planted out. This is exactly how I perceived European culture: pot-bound; shackled, limited, exhausted by itself, circling around itself in a system of old ideas, axioms and assumptions. That’s why I took myself out of this culture like a potted plant that you plant out and left for the wild nature of Connemara.”

The philosopher recognised early on that beliefs are actions, that our actions are shaped by what we believe. He therefore saw the wrong path taken by mankind as early as the creation story in the Bible, in which God called on mankind to subdue the earth: Rule and subdue the earth. Make use and benefit. He believed that the failing human species had taken a completely wrong turn onto the road to destruction at the latest in the Age of Enlightenment, when it began to absolutise rational positivist thinking, the sciences, the material world and the pursuit of profit, thus dangerously restricting our perception: trees became cubic metres of wood, rivers became transport routes, cattle became hectolitres of milk and tonnes of meat, the landscape became building land and land became capital. According to John European culture, a culture in break-down, had to be laid on the psychiatrist´s couch to take it back to it´s infancy to see where and why it went off the rails.

Free from illusions John saw humanity as a deadly disease for the planet: “We have become to this earth what AIDS is to the human body.” He recognised recovery and salvation in a radical change of perception and consciousness. He himself, freed from restrictive imprints, looked deep beneath and behind the surfaces. He practised his awareness by sitting for hours on end, meditating and immersing into himself. He did not tell others what to do. He gave no instructions, no directions, he never held individuals accountable. He did not give us a how-to-manual on how we could change and refine our perception. Instead, he described his experiences, such as the realisation on a pure, clear morning looking at the mountains of Kerry:

“. . . the subjective-objective divide is a dispensable piece of mental machinery, the mechanism of our alienation, turning us into spectators. The fourteenth way of lloking at a blackbird or at Torc Mountain is to remove the one who looks from the looking. . . Seeing is.”

When John Moriarty gave up his university career after seven years, it was also a rejection of the vocation of teacher. He expressly did not want to be a teacher, let alone a leading figure or a guru. He rejected pupils, disciples at best, he accepted creative contradiction at eye level.

Still, the Kerryman encourages us to see through the surface of the conceptually configured world and to recognise things as they are. He hints at how it is possible to connect with nature without conceptualisation or illusion: ‘I practise being a standing stone; standing still, not thinking, not moving’ – which is a special kind of meditation, one that can reduce or abolish the subject-object relationship. Or: “I think with the mountains and the rivers – not about them.” John at times asked the mountains to come with him to keep him real.

This form of perception, a kind of paradisiacal perception, he named The Silver Branch Perception after an old term from Celtic mythology – a way of seeing that allows and unites all species, races, worlds and other worlds and that would lead to a new way of being on earth. It would be the return to paradise lost.

BACKGROUND INFO

Reliable information about John Moriarty and his complete works in English can be found here:

* The official website for John Moriarty, just launched recently: www.johnmoriarty.ie. The website informs about a great opportunity to learn more about John´s life and work: The John Moriarty Festival will take place from 21 – 23 June 2024 in Moyvane, Co Kerry, Moriarty´s birthplace. The event will be a highlight with many excellent speakers. Check out here.

* The John Moriarty Institute for Ecology and Spirituality: The JMI is dedicated to publicising the life & work of the philosopher and supporting the ecological and spiritual concerns of John Moriarty. The Institute’s website is a rich source of texts, photos and videos by and about John. Website: Click.

* The JMI also runs a very active Facebook group with daily posts on John Moriarty. Because it’s for a good cause, here’s – as an exception to our policy – a link from Irlandnews to the John Moriarty Facebook-Group. Click.

* The Lilliput Press: John Moriarty’s books (so far all in English) are published by the Irish publishing house The Lilliput Press in Dublin. You get a good overview of John’s books and audio books on the publisher’s website. Website: Click.

In his life, John Moriarty broke the boundaries of conventional perception. With the destruction of all thought structures, the rejection of a sociological-cultural self-definition, with the unprotected journeys into psychological no man’s land and into unknown territories of the unconscious, the mystic-philosopher also gave up all shelter and safety for his psyche and his soul. He travelled for a long time without protection, exposed to wind and weather in both the literal and figurative sense. He made considerable mental and physical sacrifices to recognise his truth, he paid a price.

John was mostly alone in his life, sometimes he was lonely. He said about this: “I have been, intellectually, very alone. Someone has said that solitude is the glory of being alone, loneliness is the pain of being alone. I have experienced both the glory of being alone and the pain of being alone – and the pain of being alone is mostly to do with not being able to share your ideas with other people.”

At the end of his life, John Moriarty longed for shelter and shared ideas again. He returned to the Christian faith and to his roots – to a faith based on nature and ritual that did not need the church. The plans for the Christian hedge school Slí na Fírinne remained wishful thinking. John Moriarty died in 2007 at the age of 69, and with him the project. How would he have acted as the leader of a Christian community, he who no longer wanted to be a teacher and yet was a great teacher – who tells us in his books and lectures, even after his death, that we can change our perception and find new, better ways of being.

An anonymous Irish reader who studied John Moriarty’s books for two decades recently summarised the author´s current relevance in a forum post:

“John’s books are probably some of the most important works you can read in the 21st century Ireland. His walk into the hidden realms of the philosophical framework of the Irish society, mind and psyche are a necessary and important journey to take if you wish to understand the chaos that is abounding at this time. He foretold not only what was to come, he also opened up regions for future thinkers, artists, poets, and writers to navigate for others. I have been deeply influenced by his work and have shared this with many who feel the same. His growing influence is a testament to the investment and commitment he made with his own life to find understanding and resurrect the true lineage of living and being here and now.

John Moriarty’s work is most definitely a framework for future foundations for Irish life and thinking. His work has brought my life a great sustenance and has offered me a doorway into many regions that were never explored before but also a resurrection of ancient thought systems that would allow for a way of living that is equal to our surroundings.

John’s writings are a true and holy sanctuary of knowledge, once read, they bring an ancient peace back to the fore of the heart and soul and what it is to be Irish.”

Darkness has now fallen over the valley. It is raining lightly. Patsy steers the quad bike uphill through water-soaked meadows and brings us back to the boreen safely. There is a planning application next to the field gate. A family from Killarney has bought the land in Cummeen Upper and wants to build a house there. Patsy’s sheep will probably have to move too.

To be continued

(The next story in this series will be written by author Mary MacGillicuddy. Mary knew John Moriarty well and has been studying his work for many years.)

You can support us. This new series of articles about the Irish philosopher and msytic John Moriarty can be read free of charge – as well as all the other stories of this web magazine. They are our present to you. There is no paywall und no distracting advertising. We do not make use of cost-effective Artificial Intelligence. Every story is being researched and written by human beings.

🤔

If you like and appreciate this work, you can support us and help offset the technical costs – a growing four-figure sum every year – with a donation. We appreciate every gesture. If your finances are tight, please do not give money. Support us with your talents. Here you can make your donation.

Photos: Pictures of John Moriarty with friendly permission of The John Moriarty Institute.

Title-Photo: The Lilliput Press Dublin;

Photos of Cummen Upper: Markus Bäuchle

This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

Leave A Comment