This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

Part 5 of the Irlandnews series on John Moriarty

:: Zur deutschen Übersetzung: Klick

:: The whole story about John Moriarty you may find here : Click

In today’s part of the series about Irish philosopher and writer, poet and mystic John Moriarty, Kerrywoman Amanda Carmody is sharing her memories of the great philosopher who was her beloved uncle. We asked Amanda to write about John Moriarty for Irlandnews to intoduce this deep thinker to a wider German audience. Amanda describes the unconventional hermit John as a gentle, kind and wise man who was always present in the moment: “I loved John dearly. I love that he was as he was, he experienced good days and bad days, he lived his contradictions and imperfections as honestly as he could, and he integrated his wildness in a radically non-violent way.”

Amanda explains the main features of John´s work, which 18 years after his death is more relevant than ever. John Moriarty saw the state of our planet and our current multi-crises as mapped and present in all of us. His credo: We are all related to each other, humans, animals, plantsand rocks and shall live peacefully together accordingly. Our beautiful planet Earth is the true paradise – we just have to learn to recognise it.

Amanda, you are the niece of John Moriarty; your mother Phyllis is John’s sister. As a child you spent a lot of time with your uncle. His thinking and his view of life have deeply influenced you. Today you take care of John’s philosophical and literary legacy and work to make his valuable knowledge accessible to many people.

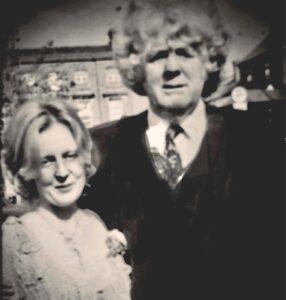

Amanda Carmody and her mother Phyllis, sister of John Moriarty. Amanda is a niece of John Moriarty, a daughter of his youngest sister, Phyllis. She spent the first few years of her life living at the Moriarty home place at Leitrim Hill. Her connection with John began on his visits home and deepened in later years when he returned to live on the side of Mangerton mountain, near Killarney. Since his death she has immersed herself in his writing. Amanda runs a very active Facebook Community Group dedicated to the wisdom teachings of John Moriarty.

Amanda, how do you remember John?

I remember John with a great sense of fun, affection and fondness. He was always full of life, attentive and present in the moment. I remember him best during three different phases of my life, as a young child, when I was a teenager and when I was in my thirties.

I was fortunate to live in the Moriarty homestead at Leitrim Hill until I started school at four years of age, my father was a university student and for the most part I lived there with my mother Phyllis and my grandparents Mary and Jimmy. Therefore, I am blessed to have been nurtured in my early years in the same place and by some of the same people and animals who nurtured John when he was a child.

I have some very simple early memories of John when he returned home from Canada to visit his parents. To me he seemed enormous, my very earliest memory of John is of him walking through the open door of the farmhouse. I was a small child sitting on the floor and John had to stoop down in order to fit through the doorway. Not only was he a tall man but he had a big frame and a huge head of wild, curly hair which gave the impression that he was much bigger than he actually was. I remember sitting on his shoulders and it seemed to me a great height, I felt as though I could touch the sky. John had an undeniable presence when he entered a room, I suppose you might call it charisma and yet that isn’t quite the right word because it was unselfconscious. Even as a small child I seemed to have had a sense of this and I would say that it was something my Aunty Babs also had, there was something very old in the way that they spoke and a dignity in how they carried themselves.

We moved to our own home nearby when I was almost four. I do remember walking the road with John at night to light the Christmas candles in the windows of the farmhouse, but I have no memory of the conversation as John writes about it in Six Stories. How strange it is now to read John’s words and to consider the relevance of his advice to little Amanda in that parable, his advice to all of us and given the character that he was perhaps there were times in John’s life when it was advice that he was giving to himself. To me it is a passage about how much we are constrained by the conditions and expectations of others.

‘And then, still on the road, knowing it with the soles of my feet, I remembered Amanda’s answer. ‘Yes’, she said, wearily, ‘everyone is shtone mad about me.’ Amanda’s weariness at being so loved. Why, I wondered. Was it that all this love coerced her? Did it suffocate her? Did it deprive her of everything except her loveliness? Was it turning her into a perfect little doll that everyone wanted to play with? Did it somehow cheat her, rob her of her had impulses to rebellion and independence? Did it rob her of so much that she might natively and naturally otherwise be? Were she to become an accomplice with them in their perceptions of her would she end up lob -sided on the side of the angels? Was Amanda being vampired by love? By a kind of love? By a kind of lovableness?’

I have such rich memories of growing up on the farm and in the fields and roaming the bogs around Leitrim Hill. Like John the place too seemed to have a character and a rhythm all of its own, unknown to me then, I now see that it was a privileged existence, it was the end of an era. The sounds, the smells and the tastes of childhood it seems never really leave because they are so deeply embedded in the psyche. The smell of fresh milk, cut hay, heather in the bog, a turf fire in the hearth, fresh farmyard manure. The sound of my grandmother calling across the yard to her hens, the swish swish of Jimmy using a saghd to cut the rushes, the rhythmic music of my mother milking a cow by hand into a tin bucket, the cows breathing and chewing the cud in their warm, sheltered stalls. The sheer magic of picking up a day-old chick or placing your fingers in the mouth of a newborn calf was just heavenly. I marvel at the freedom we then had to get to know the animals, to wander and explore along the riverbanks and fields. Then there was the taste of warm milk, freshly baked griddle bread and crushed blackberries, these things will always be with me. It is strange to know that these were the same experiences that enchanted John Moriarty growing up on Leitrim Hill.

JOHN MORIARTY – BACKGROUND INFO

John Moriarty was an Irish writer and philosopher acknowledged for his profound insights and mystical perspective on modern life. He was born on February 2, 1938 in County Kerry and died there on June 1, 2007.

More information about John Moriarty and his complete works in English can be found here:

* Amanda Carmody runs a very active Facebook community group with daily posts on John Moriarty. Because it’s for a good cause, here’s – as an exception to our policy – a link from Irlandnews to the John Moriarty Facebook-Group. Click.

* The official website for John Moriarty: www.johnmoriarty.ie. The website informs about a great opportunity to learn more about John´s life and work: The John Moriarty Festival will take place from 21 – 23 June 2024 in Moyvane, Co Kerry, Moriarty´s birthplace. The event will be a highlight with many excellent speakers. Check out here.

* The Lilliput Press: John Moriarty’s books (so far all in English) are published by the Irish publishing house The Lilliput Press in Dublin. You get a good overview of John’s books and audio books on the publisher’s website. Website: Click.

In later years John when I might be going through a hard time, he always reminded me of how loved I was by my grandparents, Mary and Jimmy. I felt a deep sense of being sheltered and nurtured by them, the place itself seems to have that effect on the people who were connected to the house on the hill, the fields, the river, the birds, the bog, the wildlife and the domestic animals. My mother told me recently that when the candles were lit in Moriarty’s windows, they were visible for miles around, this was a time before electric light came to the region. My aunty Babs, who lived and worked in England, missed home terribly at Christmas time, and it comforted her to say that “the candles are lighting on the hill tonight”. Madeline living in Lenamore could see them, Phyllis living at the end of the road could see them, and even those who could not see them knew that that would be lighting the way on a dark road at Christmas.

I cannot say that in my teenage years I was always proud of my Moriarty roots. At this time, I just wanted to fit in and be ‘normal’ and to be a Moriarty flies in the face of that aspiration. It is a mixed blessing to be born into the house of Mary and Jimmy. In retrospect John was not even the wildest member of the family, they all seemed to inhabit an inability to conform, to be fenced in or routinised into conventional ways of living. It took me a while to be at ease with this and learn to appreciate my roots in wildness. As I see it now, to be a Moriarty is to walk a very thin line between genius and madness, it is to be misunderstood by many people. Having a wild nature, heightened sensitivity, and an exceptional intellect, John struggled to find his place in the world. He worked on integrating and including the heights and the depths of his experience and accepting who he was. John writes in Night Journey to Buddh Gaia

“The longest and most difficult of journeys it is, this journey to where we are.”

Though he thrived in the academic career that he had in Canada, John eventually began to feel fenced in and he had other yearnings that he needed to pursue. He was thirty-three when he decided to opt out of academia and return to the West of Ireland. John explains that he felt pot bound and needed to be planted out and nourished in wild soil. This meant returning home to connect with his native roots and find his bush soul. By this he meant his wild and natural sense of soul outside of the societal conditioning and expectations.

Leitrim Hill was deeply embedded in John’s psyche, the wonder and the trouble of growing up there had shaped him. It was a place where the doors and gates were left wide open and at any moment a neighbour or his horse could walk through. This reflects something of John’s own nature also, there was in him no hiding from reality, no hiding from his own true nature.

Thanks to his mother there was always a welcome cup of tea and plenty of talk often with a good helping of sarcasm and humour, but she was usually not one to mince her words. One neighbour recalls “Mary was great fun, she was like the Tommy Tiernan of the townland.” Then there were other days when she would host interesting and perhaps lively conversations about religion and politics. As John wrote “ours was a house of big talk. Talk that never sickened into politeness, not even in the presence of holy things.” Naturally she worried about her son John, at first she thought he might be a farmer and take over the family farm but John had other ideas. He was to be a teacher, he went to university, he was homeless, he was a professor, he was a gardener, he was a to presenter, he was heartbroken, he was a hermit and a writer. John inherited much from his mother, his hair, his sharp intellect and his way with words. When John was home to visit there were always callers who loved the interesting conversations and discussions that would naturally flow. People like Gabriel Fitzmaurice and my father, who stayed up chatting until 5 am on one occasion and drank 22 cups of tea to stay awake. There was no shortage of vibrant conversation, forthright opinions, the laughter in the house on the hill.

Villagers of Moyvane in North Kerry: John Moriarty and Gabriel Fitzmaurice, poet, writer, broadcaster and teacher.

My grandfather Jimmy was different, his diction was slow and deliberate. English was his second language; he grew up in the Gaeltacht speaking Irish. Quite naturally he was a man of few words and much more reflective. Jimmy was a loner in many respects and seemed to love silence and solitude and time alone in nature. He was a born thinker, a sensitive soul who loved his animals as his dearest friends. He was sociable and when he would take a drink of stout or maybe whiskey from time to time, he could be persuaded to sing in the old Irish style. There was a quiet, unassuming presence about him that was very endearing.

Jimmy’s compassion and empathy with people and animals meant that the business of managing the farm mostly fell to Mary, buying and selling the animals, putting a price on them was too much for him. If an animal died Jimmy would ‘take to the bed’, if the cows lost their calves he felt it deeply. John learnt to appreciate his father’s wisdom and regarded him as one of his great teachers and so do I.

“What I learned from my father is that you don’t need to be an intellectual to be a philosopher. More often than not, it isn’t through intellect at all that deepest life in us mediates its deepest wisdom.”

I was almost twelve years old when Mary suddenly died of a heart attack. John returned to Leitrim Hill to be with Jimmy who was passionately grieving for her. It was a house immersed in deepest grief and sorrow after she passed away, her absence left a huge void in the family. Everything seemed lonely and it was as though the whole house was grieving with Jimmy, the place was very different without her in it. My sense is that this was not a happy time in John’s life either. He spent a lot of time reading, writing and out for walks on his own. John was exceedingly generous with his money and his time and even when he did not have very much to share, he would give his last. I remember the tradition of wren boys calling to the house on St Stephens Day. How delighted John was that they brought music and colour to the house and how generous he was in giving them money for the gifts of colour and song that they brought to his home. I imagine that it was not easy for John to be living back at home again after so many years away. Looking after Jimmy and bearing witness to his grief, his requiem for Mary, and his fears about crossing over to the ‘hereafter’ was something that had a

profound impact on him. In response to his father’s doubt John suggested that

“‘Maybe there is a providence in it,’ I suggested . ‘Since praying comes so naturally to you maybe you were left behind to do just that, to pray for her’. From that moment he had a purpose, and he took to it the way he’d take to saving a meadow of hay, he put everything that was in him into it. It was as if he had taken over where I had left off, just under the horizon of the world. So as to be within nearer reach of him in the night I moved my bed up into the parlour . Anxious on his account, I’d wake every couple of hours, and I’d hear him praying. These were dark January nights and listening to him I’d feel that he had rowed the house out into eternity.”

I was in my late twenties when John moved to live in Killarney, I had a home and a family of my own by this time. I developed a mature friendship with John over time, and he became something of a father figure for me. There were times when my own life was in turmoil, and I often went to John for guidance and good solid advice. Contrary to how it might appear, John was very practical and grounded when a person sat opposite him seeking advice. He was a terrific listener and non judgemental in expressing his opinion. He could also be forthright ‘Do not play the blame game Amanda’ he once advised me. “Turn off the hundred-watt bulb” he advised on a few occasions, in this he was suggesting that I take a break from being constantly alert and switched on. Sharing time with John I had an abiding sense that he knew me and understood me very well, even if I didn’t always understand myself. He knew that I often lacked self belief and confidence, and he always made it his business to encourage me. He would sometimes speak his mind when he felt I was mistaken or misguided in my opinions. John wanted me to question him and challenge him. He openly invited me to challenge him though I rarely did. How blessed I feel now that I had experienced these ordinary moments in the car, at his house, walking down the street in Killarney.

John spent Christmas at my home on a few occasions, we were able to enjoy a vegetarian Christmas dinner. He joined us for Christmas 2005, he had not been feeling well, and he told us that his doctor was referring him for some tests in Dublin. I was not overly concerned because he had been experiencing ongoing issues relating to chronic fatigue. He told us that they were investigating three possible causes of his abdominal discomfort, coeliac disease, diverticular disease and cancer. It came as a major shock to discover in early 2006 that John had cancer and the prognosis was not good. I am not sure that I handled the news very well, I resorted to a practical response, I would bring him soup and food that he could easily digest. I sometimes drove him to attend medical appointments. I think that I assumed that he would not be afraid of death and for the most part he was not. He expressed that he felt lonely at the thought of leaving the beauty of the mountains he lived in. Among other issues John was struggling with exhaustion and I recall him saying that he didn’t feel confident doing interviews because of the chemotherapy he was on, he felt that the treatment and the exhaustion were clouding his judgement. Nonetheless one of the most touching interviews he ever did with Maurice O Sullivan from Kerry Radio in the months before he died.

John expected death to arrive sooner than it did, he wanted to be conscious at the point of death. He refused heavy sedation for this reason. One morning he awoke early and looking at the Paps through his bedroom window he said, ‘Christ , am I still here!’. Not long after this he got his wish, John was conscious at the point of death and those present remember the energy in the room when he was dying. John Moriarty passed away peacefully on June 1st, 2007.

I was in the car at about 6pm when the news came that John had just died. We arrived to the house a few hours later at about 8 pm. The gate was opened, and the front lawn was covered in cars and jeeps, this instantly saddened me because I knew that John never allowed cars beyond the front gate, to him it was a sanctuary for the mosses, the insects and snails that made it their home. When I voiced this, I heard someone say, “John Moriarty is dead now.” Strangely though I never felt his absence, yes, I could no longer visit him or call him on the phone but there is a sense in which John is ever present for me. I feel fortunate to have known the ordinary John, to have enjoyed the humour and interesting perspectives. I knew him in his sorrow, in his laughter, in his awe for nature and love of people. Blessed for how often I sat on the floor from the age of three to thirty-three and how often I was a silent witness to conversations that he had with other people.

Needless to say that I loved John dearly. I love that he was as he was, he experienced good days and bad days, he lived his contradictions and imperfections as honestly as he could, and he integrated his wildness in a radically non-violent way. His reverence for life in all its varieties and mysterious forms has influenced me and he poured all of this into the books that he wrote and the stories that he told.

Amanda, did you recognize as a young person that John was a special human being who thought and lived differently from most other people?

Undoubtedly, I realised that John was an original and he was certainly unconventional, to me he was also fearless. John didn’t hold back, he spoke his truth respectfully and he spoke as one who was not constrained by an affiliation to church, state or academia. The fact that so few people understood what he was writing about meant that his work was and is still relatively unknown and undiscovered outside of Ireland. Yet his very presence, the way that he spoke and carried himself meant that when he walked into any room people were intrigued. Anyone who was fortunate enough to attend his talks wanted more and it is mostly these people who initially went on the read the books. John was never seeking fame or popularity; he turned up and told his stories to audience and for a few hours they were taken on a journey with him. In the introduction John Moriarty Not the Whole Story by Mary McGillicuddy she writes

“ To be in the presence of John Moriarty, either casually or in attendance at one of his ‘talks’ was an unforgettable experience. A tall man, unconventionally dressed, with, in the words of Paul Durkan ‘his mane of curling hair and the pain of humanity in his face’, he would approach the microphone and start to speak. No notes, no power point. The man was the message. He told stories, stories about ordinary happenings, ordinary but rich in wisdom and wonder and humour, and out of those stories he conjured a different way of being in the world.”

His books are like this though admittedly they require more effort, they cannot really be summarised or explained because they are a journey that one needs to embark on and experience for themselves. Where they lead one reader may be very different to where they lead other readers. This is because it depends on the perspective of the reader themselves as much as the text. To me this is the genius of John Moriarty, that he meets the reader where they are, at their own level and accompanies them on a pilgrimage of transformation. He says himself that his writing is an invitation to co-creation. In my own case it is probably true to say that I will never be finished with reading John as long as it still nourishes me. Spectacularly, I can read the same text or listen to the same audio after a few years and it will reveal something completely new for me. I know that I am not alone in this.

When I sat alone with John by his fireside in Killarney, he was just my uncle, a family elder that I wanted to get to know a bit better. I felt that I was heard, understood, accepted and sheltered in a way that was different to anything I have ever experienced previously. I loved that John was ordinary and he valued the company of Martin O Halloran, his near neighbour Maisie Brosnan or myself as much as the company of the elite or the celebrities he knew. John would speak as passionately to an individual who called to his home for a chat as he would to a packed lecture hall. He was not afraid to be vulnerable, to be wrong, to be challenged and he never took the high moral ground or told people what they should and should not do. He had a mind that had not rested on conclusions and was open to constantly learn and relearn, I found this refreshing. John gave his best and it was this sincerity of purpose, authenticity and compassion that impressed me as much as what he had to say. Familiar guests to his home and friends were greeted with the same warm and lingering hug or handshake and the words “Come in, you are welcome, God bless you!“

He may have been a hermit, but he was a warm and friendly one who loved to learn from people of all walks of life and he loved hearing their stories. Even when I did not quite understand what John had written, I knew there was a great depth of wisdom in his words. It was obvious to me that his life was his prayer, and his stories were his offering, an invitation to discover who we are outside of our society’s expectations. John didn’t write abstractly; he was writing from the depths of his own personal experience. It was not with the expectation of big book sales or even that he would make a profit that he wrote. He did not charge for the talks that he was invited to give but he did accept donations if they were offered. John wrote because he felt compelled to do so, in the hope that his work would nourish the reader and be a

virtue to the world. In his book Crossing the Kedron he has this to say:

“The book makes no claim to aesthetic dignity. Its urgencies and anxieties are to say something, not to say it beautifully. In that sense it isn’t so much a book as an invitation to co-creation. Its readers, should there be any, will need to co-create it. And that, perhaps, is a kind of reading that has its own peculiar excitements. But whether that be so or not, a book so classically perfect in construction and content that it resists co-creation isn’t something I have in me to write. A chaos of themes that is beginning to cohere into a common direction is all I have to offer. The hope is that such nearness to chaos will have its blessings, blessings not always at the disposal of something more ordered.”

Amanda, you have not only read John’s books but studied them attentively and deeply. What do you consider to be the most important messages in John’s philosophy?

First: Care of the earth as a living, breathing, evolving organism. Walk beautifully on the Earth and have trust in the wisdom of the universe. John Moriarty questioned the anthropocentric model, he even questioned whether as a species we are in danger of becoming extinct as a consequence of our own behaviour. He cited two ways that we can evolve, with nature or against nature, the way of inter-being or the way of dominion. The human species has mostly chosen to work against nature, to dominate and exploit the earth for monetary gain. I think of the Cree elder who warned that ‘Only when the last tree has died, and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will we realise we cannot eat money.”

John believes that dolphins and sea creatures being wiser that we are, set out on the evolutionary path of flowing with nature. The way of dominion over nature has not worked. He encouraged a deepening sense of relatedness and love for the earth just as our ancestors and the indigenous peoples of the world would have regarded her as mother, as grandmother. In Ireland she was regarded as a goddess and named after a goddess. What differs about John’s understanding is that healing the fractured relationship between humankind and the Earth needs to emerge from a deeper wisdom, from the level of the senses and soul rather than from the intellect or various modes of scientific knowing. In other words, from the heart and not the head. In order to make this shift he suggests that we must examine at our conditioned

worldview which is to rule over the earth and have dominion over other life forms. This is challenging and involves acknowledging that the path we have chosen has not worked and huge damage has been done by humanities commodification and exploitation of the earth for profit and exclusively for man’s use and benefit.

A shift in perception is what is required according to John Moriarty, a shift from seeing through a purely economic lens to pure beholding. John quotes Job 5;23:

“. . . for you will be in league with the stones of the field, and the animals of the field will be at peace with you”

and he urges us to “be in league with the Earth.” Once this internal shift dawns in us then the hope is that our behaviour will also change. John asks “What has happened to the wonder child in us?” because he understands that at a deeper level of consciousness, prior to our conditioning, we are instinctively and naturally in touch with that sense of childlike wonder that is pure beholding and being.

Second: This brings us to the Lakota words Mitakuya Oyasin, sacred words that mean we are all related. John held these words in such high regard that they are his epitaph. “Two words” he writes “that must transform Christianity ecologically, cleansing it of anthropocentrism” sacred words that a Lakota elder might use during a ritual or ceremony. I believe that this represents an overlooked aspect of John’s teaching which is his ecumenical vision:

“Seek to live ecumenically with all things.”

Western Culture needs to move away from the way of seeing the world that divides everything into “us and them” and move towards a way of “we” thinking. Can we be ecumenical with people of differing ethnicity and beliefs? Can we aspire to be ecumenical with other species and various life forms? Can we hope to be ecumenical with rock and tree and star?

Third: Put up your sword. Non-violence. What we need now is a new kind of hero, one that does not wield the club or the sword, a hero of integration and inclusion. A mythology that acknowledges the courage of the non-violent hero in our culture. This is a real challenge in the world today, it requires a radical commitment to nonviolence. Ahimsa is a Sanskrit word that refers to the ancient Indian principle and it implies striving towards nonviolence in action, deed and word. John understood that integrating and living by this principle is not an easy thing to do. He asks:

“Is psyche in us able for itself? Can it become what it is, all that it is, and at the end of the day not a hair of another person’s head will have been harmed?”

Fourth: Practice Silver Branch Perception. Practice being in paradise. John asks what has happened to the wonder child in us? What has happened to what is right royal in us? He urges “walk naked to Tara and inherit your royalty.” Central to the practice of silver Branch perception is the idea of resonance and being in tune with the music of the universe, the music of nature, the music of what happens. John Moriarty writes in Sli na Firinne:

“I practice the belief that the subatomic particles of which I am physically made are hosannas, are self -sounding quavers in the everlasting song of the heavenly hosts. Joining them, I sing with them.”

To be out of tune with nature John believes is a great illness but to be attuned to nature, to the eternal song of praise, is a marvel. To practise paradise doesn’t require any particular religious belief, if we can stop

every now and then and wait for our souls to catch up, then a moment will come when we open our eyes and see that this resonant music is everywhere, and it is in everything. We can then look at something quite ordinary and recognise its innate resonance. We arrive at a new and wonderful way of seeing and relating to the world around us. John is confident that if we practice Silver Branch Perception

then Silver Branch Morality will follow and silver branch be-ing will emerge. It is a move away from the way of dominion over the world we live in and a step towards communion with nature.

“I wonder whether I can presume that I am holy in the silver-branch resonance of my be-ing? Can I presume that all things are holy in the silver-branch resonance of their be-ing? If it be so, then if I but utter the word ‘dandelion’ in the age of the world’s night I am uttering the holy.”

Fifth: Integration and Inclusion. As a natural consequence of this you won’t feel the need to squish the spider in your bath or spray the daisies or buttercups in your garden.

“To be ecumenical with all that I inwardly am is to be ecumenical with all things. It is to already live ecumenically in the great ecumene.”

The way of suppression and exclusion does not work, cutting ourselves off from reality does not work, lobotomy he says is not the answer.

”Lobotomising the earth, lobotomising the sea, lobotomizing the psyche. Lobotomy isn’t the answer. It is trouble. Trouble altogether greater than the trouble it sought to eradicate, we must come forward from, must grow from, new beginnings… New beginnings from which to come forward springing forth. Beginnings in which integration not suppression becomes proto-typical.”

Sixth: Be embryonic. The most important question we can ask ourselves according to John Moriarty is: Am I still growing? Is my life still an adventure? “By time we have reached our twenties many of us have ceased to be embryonic to any other vast possibilities of growing. We have gone rigid”. To be embryonic is to have the unconditioned, beginners mind full of potential and possibility.

The individual journey matters in John Moriarty’s teaching not in the egocentric sense but as part of the integrated and interconnected whole. “The truth is, the deeper and the farther we journey into ourselves the more marvellous we find ourselves to be.” That which is not growing is dying and the wasteland we live in is evidence of the wasteland mindset that has prevailed. John pulls no punches in Night Journey to Buddh Gaia:

“The diminished Earth is its reflection back to us of our diminished view of it… In itself it is as tremendous and folkloric and as instinctive with wonder and terror as it ever was. And what is true of the Earth is true also of ourselves. It is to diminished seeing and knowing that we and the world have together fallen victim. Were we to outgrow this diminishment, we would once again have need of tales altogether taller and altogether deeper than current common sense.”

We need to begin to grow and outgrow in new ways so as we can evolve with the evolving Earth. “In the age of the world’s night someone willingly will become nothing and in this nothing the world re-enacts it’s beginnings. This, surely, is what happened to and in Jesus.” Not an adventure to be taken lightly but John Moriarty sees this as a natural growing process that happens organically like metamorphosis in insects or puberty in humans. This puberty however is not just a physical or psychological growing, there is also a spiritual growing that happens, and our culture fails to acknowledge. The spiritual puberty he calls the Tridum Sacrum, three sacred days understood to represent three stages of mystical growing or three stages of spiritual awakening. These are Christian words referring to the three days after Jesus left the city and crossed a little stream called the Kedron. John focuses on two things that Jesus asked of his disciples. He asked them to stay awake and watch with him and he commanded Peter to put away his sword. This is the challenge to us to stay awake and watch while resisting the temptation to strike out with the sword. It is an invitation to experience and undergo the journey.

As John understood the Christian way there are two paths that can be undertaken. One is the Christian sacramental path, and he writes about this in a little book called Serious Sounds, you might say this is the way of initiation and action. The second is the Christian mystical way and this might alternatively be called the contemplative path. It is the mystical path that John intended to teach to others. It is not a case of one way or the other, in fact it may be that one path is better suited to the individual at a particular phase of their growing. The purpose of both is to bring us to re-immersion in Divine ground or what might more commonly be called non-dual awareness. “We are caterpillars who don’t believe in Butterflies,” John reminds us that a day comes when the time is right, instinctively the caterpillar builds its cocoon and turning inwards it surrenders to the phases of integration and transformation. In one of my favourite passages John asks:

“Who looking at the yolk of a pheasant egg would predict pheasant feathers? Who looking at an eight-legged, green cabbage caterpillar would predict a white butterfly?…. We live in a surprising universe, and it would be stupid not to dispose or predispose ourselves accordingly.”

John intended to establish a Christian Monastic Hedge-school called Slí na Fírinne. Author and mythologist Martin Shaw explores what this might look like in this terrific talk which he gave in Moyvane in 2024:

Seventh: Become a great story. Because if the world is as Keats says it is, a vale of soul-making, then time spent in once-upon-a-time isn’t time misspent. After all we do live in a universe in which a caterpillar becomes a butterfly. This is why John tells stories because some of them call us into the deeper mystery of things and others awaken us from the anaesthetic of everyday hearing and seeing and knowing. “The business of stories is not enchantment. The business of stories is not escape. The business of stories is waking up.” said Martin Shaw.

“A story is great when, as we tell it, it tells us. It is great when we emerge from this telling with a deeper and a surer sense of ourselves. There is a sense in which our stories create us. Or, if you believe that a God created us, then you might say that our stories take over from where he left off – calling us into richer, greater life, they continue his work, and when they do this, they aren’t only great stories, they are sacred stories. Have you become a great story? Have you, in spite of the moral contagion that infests you, become a sacred story? Have you, instead of bringing home a myth, become a myth that will deepen itself and deepen us every time it is told?” (John Moriarty in Anaconda Canoe)

Have you become a great story? Have you become a sacred story? John says that all time is once upon a time, and this implies that the stories and myths of our culture matter and our our personal story matters also on the evolutionary trail. At the beginning of the Six Stories audio collection, John explains that they are six parables out of his own Galilee. “Six Stories, six mirrors, we all might look in because terribly now, there is a need in our culture for a turning. The question is: are you the kind of person in whom turning can take place ?’ Stories told by a fireside are never really a finished creation, they are constantly evolving and they take on new meanings and significance with each new telling and that is their great power, they are not fixed and they can reveal as much about us and the world that we live in, they enchant us in a way that science or reason cannot. Mary McGillicuddy, author of John Moriarty Not the Whole Story, puts it very well, our lust to explain things shuts us off from our deeper capacity for wonder:

“In our world, we seem to have spent the entirety of our history in killing dragons and in building walls while all the time failing to acknowledge that the dragon is within, always ready to erupt, and that walls are worse than useless, they are utterly destructive. “Modern humanity,” Moriarty said, “is destitute humanity”, not simply because we are in denial of instinctive nature in us, not simply because we catastrophically exploit the planet, but because of a further loss that he believes we suffered once we came into the Age of Science and Reason. Towards the end of Dreamtime, he wrote: “Nowadays in the West we are, quite literally, corrupted by a lust to explain things. Our lust to explain things veils things.”

Eigth: Canyon Christianity. This is quite a challenge to understand. It basically is a symbolic journey to the bottom of the Grand Canyon by a trail called Bright Angel Trail. This is the Christian trail reimagined, not just at the individual level but at the level of evolving human consciousness, the evolving Earth and all of creation. It is a journey back and down through the piled layers of our collective evolution to the deepest part of the Earth where the Colorado River flows. John sees this as a trail back to our beginnings, to the source of life so that we might start afresh. This time leaving the war chariot and the sword behind we can hope to emerge non violently, non-dominantly, leaving nothing suppressed or buried in our wake. It is about a trail down to a depth where I is we, and rising to a height where I is we is what he is proposing:

“The challenge to us is INNOVATION, fully acknowledging that Jesus geologically endured the evolutionary mutation of Labyrinth into Bright Angel Trail, fully acknowledging that Jesus claimed the whole Canyon for culture, the whole psyche for sanctity.”

Given that John is talking about innovation and not re-formation, he gives the Earth a name that reflects this, emergence into a new relationship with the great and sacred Earth, he names her Buddh Gaia.

“In the end, we should be thinking of doing what we can do, we should be thinking of brightening our galaxy.”

Buddh Gaia implies an enlightened Earth or a brightened or enlightened way of relating to the Earth.

“Michelangelo released Bacchus, a god who is latent in it, from stone. Cambodian sculptors released the enlightenment that is native to it from stone. Time to release the Earth Goddess, Buddh Gaia, from stone. Only not of course from stone. The thing finished, stone chipped away, will continue enthused by the Divine within itself. And so, to anticipate there She is, the Revealed Wonder, first sight of Her

assuring us that we are BUDDH GAIANS.”

Why? Without vision the people perish. John cites the Maitri Upanishad “As is thy thought, so dost thou become; This is the everlasting mystery” Faith has its reasons, thoughts become reality, creation first happens in the imagination, and this is why John Moriarty believes that we need to concern ourselves with the nature of mind. Dissolving old habits of mind requires vision. It is no longer adequate to aspire to paradise regained, we must aspire to paradise without walls, we must aspire to where we are. Because John would say that where we are, had we the eyes to see, is the highest divine. All otherness is in us. And that otherness is broken down in the intense, immense purifications of the mystical journey.

“We have no need, not now, not ever, for a new heaven and a new earth. We only need eyes to see that every bush is a burning bush, burning with green fire, with red fire, with jewel -blue fire, with fire we haven’t senses or chakras for.”

John Moriarty describes himself as a Dreamtime philosopher. He is content with two ways of doing philosophy, the Celtic way and the Christian way. “Call them, if you wish, the Dreamtime way and the contemplative way. The task of the Celtic philosopher- poet is to keep the path to Connla’s Well open. The task of the Christian philosopher is to cross the Kedron with Jesus.” John Moriarty shines a light on a forgotten trail that Jesus pioneered, and his writing is an invitation to experience, it is open and available to people of all backgrounds, all religions and none: “As for Christianity having lost its original will to adventure: is it not we, the peoples of the West who have lost that will? And have we lost it because we have lost the vision that would inspire it?”

Amanda, you mentioned this before: At the core of John´s work is a special way of perception, which he called “Silver Branch Perception” with reference to Irish mythology and the Voyage of Bran. Can you further explain what it means?How can we practise it ourselves?

John calls the mindset that commodifies nature our Medusa Mindset, he draws our awareness to a mode of seeing that perceives the natural world in a purely economic way. Just like the mythical Balor who caused havoc with his evil eye in ancient Ireland, our way of interacting with the Earth turns it into a wasteland. These are both mythical characters who destroy everything that they gaze upon by turning it to stone. In his autobiography John reflects:

“In the light of our common commercial day we look at a cow and we see kilos of meat, we look at an oak and we see planks of timber, we look at the world and we see land, we look at ourselves and we see workforce and manhours. How threatened by the Grail Quest, how threatened by the recovery of vision, is this, our titanically contrived world? Probably not at all, given how great is its ascendancy over eye and mind…. In the way that an open hand, generously receiving and generously giving, can contract into a fist, so, in eye and mind, can life in me contract to suit the requirements of a production line.”

This is the very opposite to Silver Branch Perception as John proposes we practice it.“Call it silver-branch perception. Call it paradisal perception. Indeed, instead of thinking of it as a particular place, I think of Paradise as a mode of perception, a thing possible in no matter what place.”

The author Manchán Magan narrates and explains some beautiful passages from Invoking Ireland about Silver Branch Perception:

Amanda Carmody´s memories of John Moriarty to be continued

You can support us. This new series of articles about the Irish philosopher and msytic John Moriarty can be read free of charge – as well as all the other stories of this web magazine. They are our present to you. There is no paywall und no distracting advertising. We do not make use of cost-effective Artificial Intelligence. Every story is being researched and written by human beings.

🤔

If you like and appreciate this work, you can support us and help offset the technical costs – a growing four-figure sum every year – with a donation. We appreciate every gesture. If your finances are tight, please do not give money. Support us with your talents. Here you can make your donation.

Photo credits: Photos of John Moriarty with friendly permission of Amanda Carmody; this and other footage is available on the website www.johnmoriarty.ie.

This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

Leave A Comment