This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

This was The Burren Action Group (from right): James Howard, John O’Donohue, Lelia Doolan, PJ Curtis, Finola McNamara, Patrick McCormack und Emer Colleran . . . (Extract from the Clare People regional newspaper)

Part 7 of the article series on the Irish philosopher, poet and priest John O`Donohue (1956 – 2008) focuses on his work as an environmental activist and his criticism of tourism and tourists.

For many years I have quided people on foot to particularly unspoilt, magical and beautiful places in Ireland’s countryside. The offer to reconnect intensively with the landscape, plants and animals in the fresh air, under the open sky, outdoors, was often gratefully accepted and just as often interpreted idiosyncratically.

The wide view of fascinating landscapes sometimes provoked the desire to take possession: “I would like to build a house here”. Nature is often seen as a resource to be exploited, to be materially transformed into capital, profit, status and pleasure. The landscape is reduced to dead matter. It is perceived as land for building, as a reservoir for real estate, as a recreational space for holidaymakers and excursionists.

In view of the human urge to expand, there is rarely a long discussion today when a piece of remaining nature is to be turned into another building site. The soil gives way to concrete, the outside becomes another inside – into which we retreat from nature.

Part 7 of the Ireland News series on John O’Donohue

- Click here for the overview: All articles about the life and work of John O’Donohue.

- Click here for the book list: The books of John O’Donohue.

Some people still experience the landscape as alive, as animate, some as inhabited by gods. They can connect with the myth, the ancient story from the time when humans and animals were not yet divorced from each other (a thought of Claude Lévi-Strauss).

John O’Donohue was one of these people. His deep perception of the landscapes of the soul, of the living sacred nature, drove the young priest in the early 1990s into passionate and courageous resistance to defend the natural world in his homeland, The Burren.

For ten years, a small group of environmentalists, led by local eco-farmer Patrick McCormack, fought against all of official Ireland and its institutions to prevent a major tourist project in The Burren. The government, the major political parties, the farmers’ unions, the church and even the powerful football association GAA, had all rallied behind the plan to build a huge visitor centre at Mullaghmore, the sacred mountain at the centre of the primeval karst landscape of The Burren. The Mullaghmore Interpretative Centre was supposed to attract hundreds of thousands of tourists to the almost untouched landscape in County Clare, bringing money and jobs to the remote region.

Seven activists formed the core of The Burren Action Group: micro-biologist Emer Colleran, local farmer and poet Patrick McCormack, activist Finola McNamara, producer PJ Curtis, journalist and producer Lelia Doolan, local farmer James Howard and priest John O’Donohue. They were eventually even liable with their own fortunes in the long court case against the Burrens’ sell-out.

On 30 January 1993, Michael Finlan wrote a portrait of the eloquent activist priest John O’Donohue in the Irish Times:

“It was this passion [for the landscape] that caused him to become part of the Burren Action Group two yeas ago when the word first came out that an interpretative centre was planned by the Office of Public Works to be built near Mullaghmore, the truly unique mountain that some regard as the very soul of the Burren. (As it happened, he was standing in for an ailing priest in Carron in the Burren at the time and was at the first public meeting when the plans came to light). With some fury he took the microphone and inveighed against the proposal describing it as „an act of blasphemy“.

He is now the chairman of the Burren Action Group and, recalling that night, he says:“One of the things that really frightened me and one of my reasons for getting involved in the group was that I felt that the west of Ireland was now up for sale. It could be turned into a playground for saturated Europeans, They´d fly in from Germany or somewhere on Friday evening and be back in their offices on Monday morning. If that type of tourism develops, the self-respect of the natives will really go down. We´ll all become objects that the tourists will come to look at and say „see, some of the species are still not extinguished.“

After ten years of seemingly hopeless struggle, the courageous Seven of Mullaghmore won one of the greatest victories of the Irish environmental movement ever in the spring of 2000. They had managed to turn public opinion. Ireland’s Supreme Court ordered the project operator, the government-owned Office of Public Works (OPW), to apply for planning permission. After that, the entire project was brought down, all traces of the construction work that had been started on their own authority had to be completely removed.

I visited Patrick McCormack in his house at the foot of Mullaghmore. The rocky landscape in the East Burren was spared the big tourist centre. The eco-farmer and his wife Cheryl own the house, which gained fame as Father Ted’s House in the popular sitcom Father Ted in the 90s. They attracted a lot of attention and also a lot of tourists to the area. Today, the McCormacks suffer from the constant tourist siege in front of their driveway. They want peace and quiet, more distance and respect.

The family has used the seclusion of the pandemic to rethink, question and refocus. Patrick says today, “It started very innocently and then it went too far. It’s hard to keep a balance. We are tackling it. Jesus said heal thyself.” The McCormacks see their future entirely in organic farming.

Why did “the Mullaghmore miracle” happen 20 years ago, I ask Patrick. From the distance of two decades, the free thinker attributes the success primarily to two causes. The rather cryptically formulated: “A few good men went over to the other side”. And: two authoritative men were at the right age for an unpopular decision and in the right place at the time: the priest John O’Donohue and Judge Costello. That is Patrick McCormack’s modesty. Not a word about his own role.

Mullaghmore: A Brute Tribute of Respect to Beauty

As the Burren nature suffers more than meets the eye – it is massively over-fertilised, polluted with herbicides and pesticides, the once fish-rich lakes are almost empty – and although the struggle against the tourist center polarised and divided the people of the area: Patrick McCormack remembers the work of the Burren Action Group with good feelings: “It was, as Robert Frost would have said, a brute tribute of respect to beauty”.

Mullaghmore was also a great victory for John O’Donohue who, as Chairman of the Action Group, was instrumental in steering the dispute to Ireland’s highest court, the Supreme Court. John had an ambivalent attitude to tourism – an experience I myself have been well familiar with. John brought tour groups into the country to take them to ancient sites of Celtic and Christian culture, to holy springs and to the mighty cliffs in County Clare. In doing so, he at least pleaded for the right measure and distanced himself decisively from destructive mass tourism.

His friend Patrick McCormack led John’s groups into the limestone landscapes of Mullaghmore for many years. One walked mindfully, carefully and quietly. Nevertheless, Patrick McCormack concludes today: “The tourist streams of lost souls destroy these beautiful, unique places. I even found that groups we brought to the sacred places disturbed these places sensitively. So we have to be very careful.”

John O’Donohue’s critical view of tourists and tourism flowed into his essays and his poetry. In the poem “Outside a Cottage” from the book Connemara Blues (dtv 2001, page 145), he describes photographing tourists who are dropped off by bus in front of an old cottage in order to secure picture trophies of the ruin, which they then take back home as proud spoils. In the poem, O’Donohue flatly denies the souvenir hunters the ability to sense, comprehend and understand the reality of the place in its depth, or to perceive the continuing presence of those who lived and worked there in a pre-tourist era.

Today, 20 years later, we are one step further – if not three or four, in the wrong direction probably. The struggle to protect a living, soulful natural space and save it from unlimited human exploitation can no longer be fought with emotive arguments. Hard “science-based” arguments about compliance with EU environmental standards and Irish environmental law are among the weapons of choice. Nevertheless, the chances of success for the protectors and preservers have remained comparatively small.

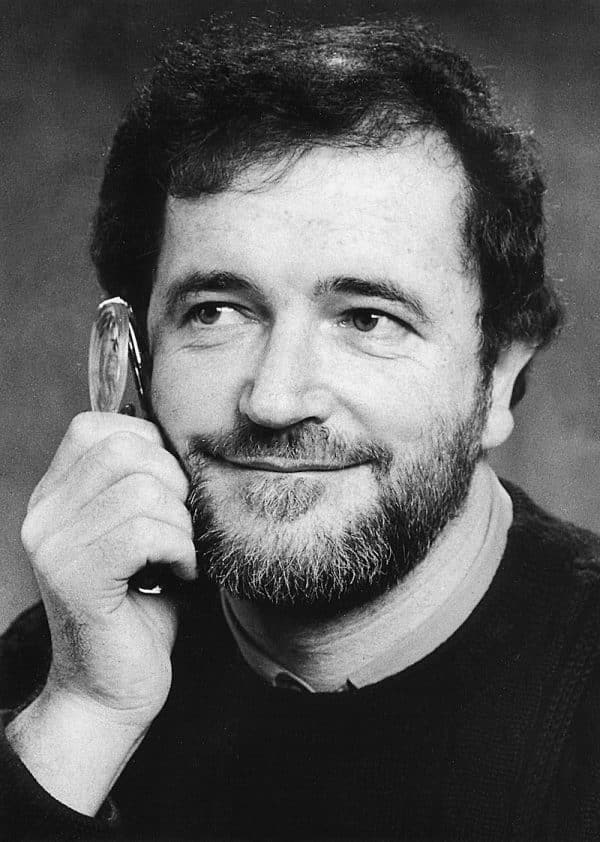

John O’Donohue in 1999. Photo: dtv

On John O’Donohue, writer, poet, priest

John O’Donohue (1956 – 2008), grew up on a farm in a limestone valley in the Burren, County Clare. The eldest of four siblings, he became a priest, later a writer, philosopher and poet, environmental activist, life teacher, speaker, mystic and humanist. With Anam Cara, The Four Elements (published and available in German by dtv), Eternal Echoes and Divine Beauty he wrote international bestsellers. He loved human existence in all its facets. His great theme was to live life to the fullest without fear. He considered unlived life to be the maximum transgression of being human. In books and lectures, John encouraged people to courageously live the life they wanted and would love. It was important, not only to dream one’s dreams but also to realise them and thus find one’s destiny – free from fear and from the heart.

O’Donohue was a free spirit who thought Celtic as well as Christian spirituality, the mysticism of Eckhart and the philosophy of Hegel. He saw us, the living, walking on the shore of the great sea of the invisible, the imagination creating the bridges from the visible to the invisible world. He understood the deep human longing for belonging in an increasingly meaningless material world and was convinced, that human beings can overcome the fear of death – because it is a progress, not an end. His headstone reads, “Their lives have changed not ended.”

I often think of this man who taught me a lot about life, the soul, Celtic spirituality, nature. I never met him, I read his books. How often I heard his words about the soulful landscape when I walked through the rocky bog. Felt his wisdom when I moved through the mountains, understood his deep unity with nature when I stood by the sea and looked west. On 1 January 2021, John O’Donohue would have turned 65, had he not died unexpectedly 13 years ago. I would have loved to have met him. In November 2018, I started researching John’s life. It began by chance at his grave in Fanore in County Clare. I am reporting on the results of this search here on Irlandnews.

The most inappropriate tourism project since Mullaghmore: Dursey Island

The “most inappropriate large-scale tourism project since Mullaghmore”, according to Ireland’s most important environmental activist, Tony Lowes, has been in the pipeline for three years in West Cork, at the tip of the Beara Peninsula: The offshore Atlantic island of Dursey Island is to be connected to the mainland by a new, efficient cable car, and the transport capacity of the hitherto rather bizarre tourist attraction is to be increased more than tenfold.

At least 80,000 people are expected to visit Dursey Island per year, travelling the entire length of the Beara Peninsula. A large visitor centre with a restaurant, sun terrace and souvenir shop is planned to be built on the mainland at the Dursey Sound, and a large car park would be able to accommodate 100 cars and several tourist buses. The narrow road out to Dursey Sound is to be widened, an electronic traffic guidance system is to coordinate access to the Beara Peninsula from Glengarriff.

Dursey Sound fairground: What looks like the tourist sell-out of the most beautiful peninsula in the southwest is widely applauded and loudly called for by the public.

Many residents and businesses from Bantry to Dursey Sound hope to get a profitable piece of the tourist super-cake. So far, there is hardly a trace of resistance. The poetic and powerful voice of John O’Donohue is missing in West Cork, and has long been missing throughout Ireland. Only a few environmental activists from Friends of the Irish Environment, An Taisce and Birdwatch Ireland are willing to take up the fight for the natural world, for Ireland’s last choughs and against the exploitation of Dursey Island.

Wonders never cease …

- Click here for the overview: All articles about the life and work of John O’Donohue.

- Click here for the book list: The books of John O’Donohue.

- Copyright: © Markus Bäuchle 2021. All rights reserved.

You can support our work with a donation

Notes and photo credits

- Photos: Markus Bäuchle, with the exception of:

- Black and white portrait of John O’Donohue: dtv.

- The shot of John O’Donohue in the Burren from 1997 is from Hessischer Rundfunk documentary Ireland’s Lonely West – A Journey through Connemara with the Priest and Poet John O’Donohue (1997). The almost one-hour film by Meinhard Schmidt-Degenhard is a unique document. It introduces John O’Donohue in his native Clare and his adopted home in Connemara. O’Donohue talks about his writing, his feelings and thoughts as well as his relationship to the Church in his best German, shortly before he becomes famous. Meinhard Schmidt-Degenhard spoke with John O’Donohue after his estrangement from the Catholic Church and a few months before the publication of his bestseller Anam Cara. Thanks to Hessischer Rundfunk (hr) for the screenshots from the film. (© Hessischer Rundfunk – www.hr.de )

- The newspaper clipping is from the Clare People newspaper. The page hangs as a framed picture in the McCormacks’ home.

- A sensitive film portrait of the Burren, the Burren farmer Patrick McCormack and the struggle against mass tourism in the Burren was made by director Katrina Costello with The Silver Branch. More Details here.

To be continued

This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

Great history and insight to the falsity of tourism as “presence” in such a vast and eternal landscape. But ohhhh, when you do experience that fine moment, a wonder-filled presence, echoes of our ancient past as feet navigate the hidden contours of the limestone…magic. Thank you, Markus.

Hello Markus Bauchle,

I am a Theater Professor in NY and have been a great fan of John O’Donohue’s writing. Are you still adding to your story about him?

Thanks!

Prof. Susan Courtney

Hi Susan, thank you for your interest. Yes, I am working on some new stories. All the best, Markus