This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

Joe worked shifts. He often came home after midnight. When he made himself a cup of tea before going to sleep, he would usually see a second light burning through the kitchen window at the end of the village: John would still be working, too, there in the old cottage, in the Tooles’ former shop on what used to be the road through the valley to town. Joe and John liked each other, they discussed many a night to “solve the problems of this world”. Whenever John was home at his retreat in Connemara, after often being absent for weeks at a time, they would sit together again. Usually in John’s living room, “John with a glass of red wine, me with a cup of tea”, as Joe fondly remembers the deep and cosy conversations.

Part 4 of the Ireland News series on John O’Donohue

- Click here for the overview: All articles about the life and work of John O’Donohue.

- Click here for the book list: The books of John O’Donohue.

In that summer of 1995, O’Donohue seemed “shaken to the core” to his neighbour. Bishop James McLoughlin had given John a choice: Either write books or be a priest. John wanted to be a priest at the time, but at the same time spend more time writing. He had already written a doctoral thesis on the German philosopher Hegel and some essays on the elements of nature. In 1994, the then small Irish publisher Salmon had published his book of poetry Echoes of Memory. It already contained the later famous poem Beannacht for his mother Josie. Now John wanted to try his hand at a larger work. He had something to say, he was full of ideas and insights, full of imagination and inspiration. But the Bishop of Galway refused him a half-day post. He gave him a choice instead.

O’Donohue decided – as friends know – with a heavy heart not to take up the post and to try his luck as a writer. He accepted the existential conflict. The momentous decision meant that he would lose his spiritual home, the church, and also that he would no longer receive a salary from the church. He was on his own.

Taken and shocked

I visited the village in Connemara where John had bought an old house back in 1990/91, in September of the Corona year 2020. That was almost 13 years after John’s death. The house looked as if he had just left it briefly to go shopping. I spoke to people in the village, I met old neighbours who knew John. I will protect the place in the interest of John’s family and that of the villagers, I will not mention its name or describe the direction. I also ask all readers to respect this and not to go looking for it. The old retreat is truly not a museum.

“Taken and shocked” was how John appeared to his neighbour Joe when he returned from talking to the bishop that summer of 1995. Swiss friend H.R. Hebeisen¹ says that John was “pretty much out of his shoes” at that time, according to his own descriptions. The man who was soon to ride the waves of success was caught in an existential conflict. And he had to see how he could earn a living. He took a teaching job at the Galway Mayo Institute of Technology, teaching humanities, and he was now living in his old cottage in Connemara.

But why did his path lead him away from the Catholic Church, away from the priestly profession? Was it only the conflict with the bishop?

John belonged to a young, freer-thinking generation of Irish priests who had problems with rigid Irish Catholicism and repeatedly questioned or even challenged the authority of the authoritarian Catholic hierarchy. The young pastors created a counter-image to traditional priestly strictness and rigidity. The fact that one was more likely to meet the young priests in fisherman’s jumpers than in black suits with priestly collars was only the outward expression of a generational conflict that was being fought out over doctrinal opinions, lifestyles, professional understanding and world views. Many of these young priests questioned the Church’s attitude towards women and the institution’s hostility towards the body and sexuality, they doubted celibacy and had a different attitude towards birth control than the Church superiors.

O’Donohue responded to American journalist Diane Covington in April 2007 in a profound interview for The Sun Magazine² about his departure from the church:

“It was a difficult decision, and it did take years to make. I suppose the oxygen had become too scarce. I also found myself diverging from quite a few of the teachings. The final straw was acquiring a new bishop who exhibited and exercised a strong chemical hesitancy to my theological viewpoint. Once made, the decision brought me great peace of heart.”

Diane Covington followed up and wanted to know why John attested to the Catholic Church having “a pathological fear of the feminine”. He replied:

“I do not trust the Catholic Church with Eros. I never did, even when I was a priest. The Church does have a pathological fear of the feminine. It would sooner allow priests to marry than it would allow women to become priests. This awful mistrust of the feminine goes all the way back to Genesis, where Eve is blamed for offering the apple to Adam. And the doctrine that a woman, after giving birth to a child — the most beautiful thing a human being can do — has to go to the Church to be cleansed: this is a demonization of women that I cannot understand.

All extremes create a mirror of themselves. So when you have the demonization of the feminine, you also have the creation of the ideal feminine type: Mary as the perfect woman, on whom no stain of mortality — or complexity — was allowed to fall. None of the awkward, subtle, different, or dark faces of the feminine were allowed near her image. I think it’s a shame, and it has consequences. I think the Church is in danger of losing women. As I’ve said for the last twenty years: if tomorrow all the women in the Catholic Church decided to walk, the Church wouldn’t last three months.”

John’s university friend, the priest and columnist Kevin Hegarty⁴ wrote in the Mayo News at the turn of the year 2007/08:

“After ordination, John honed his intellect in the strict atmosphere of a German university. On his return to Ireland he combined lecturing with some parish work. For people jaded by the blandness of conventional Irish Catholicism, he opened up new vistas of exploration and experience.

His ecclesiastical superiors became suspicious of his growing reputation. They sought to clip his wings by imprisoning him in a busy curacy where they hoped he would have less time for flights of fancy. . . .

John took the brave decision to leave the comfortable clerical zone and strike out on his own. From this decision has flowed a career of sparkling lectures and thought- provoking books. He has an audience that spans a huge range of human experience from ageing nuns to exuberant eco-warriors.”

Fellow theologian and columnist Liamy Mac Nally wrote about John in January 2008, also in the Mayo News:

“He thought and taught outside the box, yet he brought people back to their roots, ever the radical. When such a highly gifted spirit is endowed to the Church the only requirements are time and space. Ordained, he was more a Christ man than priested.”

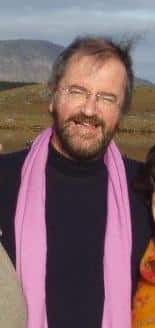

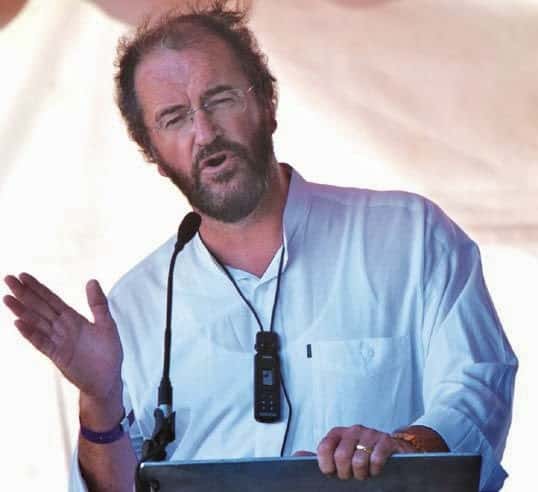

Anglican minister and journalist Martin Wroe (pictured right with John and Pip Wilson at the 2007 Greenbelt Festival; photo: Pip Wilson) wrote in The Guardian after John’s death in spring 2008:

Anglican minister and journalist Martin Wroe (pictured right with John and Pip Wilson at the 2007 Greenbelt Festival; photo: Pip Wilson) wrote in The Guardian after John’s death in spring 2008:

“He returned [from Germany] to mix lecturing in philosophy with parish life. His ecclesiastical superiors were suspicious as much of his personal charisma as of his inclusive theology. In turn he was sceptical of religious leaders who ignored the essential mystical flame of faith in favour of what he called ‘manufactured coherence’. In retrospect, it is surprising he remained in the church as long as he did, but those who met him testified that he grew into a kind of spiritual bard, a priestly troubadour speaking one day at an Oxford college, the next at a rock festival.”

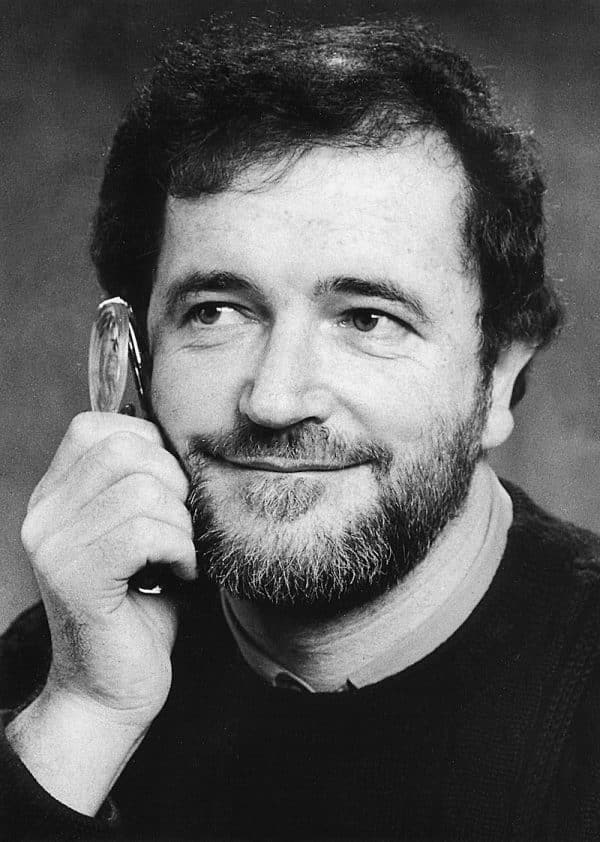

John O’Donohue in 1999. Photo: dtv

On John O’Donohue, writer, poet, priest

John O’Donohue (1956 – 2008), grew up on a farm in a limestone valley in the Burren, County Clare. The eldest of four siblings, he became a priest, later a writer, philosopher and poet, environmental activist, life teacher, speaker, mystic and humanist. With Anam Cara, The Four Elements (published and available in German by dtv), Eternal Echoes and Divine Beauty he wrote world bestsellers. He loved human existence in all its facets. His essential topic was to live life to the fullest without fear. He considered unlived life to be the maximum transgression of being human. In books and lectures, John encouraged people to courageously live the life that they wanted and would love. It was important not only to dream one’s dreams but also to realise them and thus find one’s destiny – free from fear and always from the heart.

O’Donohue was a free spirit who thought together Celtic and Christian spirituality, the mysticism of Eckhart and the philosophy of Hegel. He saw us, the living, walking on the shore of the great sea of the invisible, the imagination creating for him the bridges from the visible to the invisible world. He understood the deep human longing for belonging in an increasingly meaningless material world and was convinced that human beings can overcome the fear of death – because it is a progress, not an end. His tombstone reads, “Their lives have changed not ended.”

I often think of this man who taught me a lot about life, the soul, Celtic spirituality, nature. I never met him, I read his books. So often I heard his words about the soulful landscape when I walked through the rocky bog, felt his wisdom when I moved through the mountains, understood his deep unity with nature when I stood by the sea and looked west. On 1 January 2021, John O’Donohue would have turned 65, had he not died unexpectedly 13 years ago. I would have loved to have known him. In November 2018, I started researching Johns life. It began by chance at his grave in Fanore in County Clare. I am reporting on the results of this search here on Irlandnews.

He left without applying for laicisation

It was a difficult farewell: John O’Donohue himself pointed out what made his departure from the Church so hard for him. There was much about the Catholic Church that he loved. In conversation with Diane Covington², John explained: “I think the seven sacraments are the most beautiful liturgical rituals. The Christian mystical tradition is populated by such giants as Meister Eckhart, John of the Cross, Hildegard von Bingen, and Julian of Norwich. The dogmas of the Catholic Church are sophisticated, poetic, speculative doctrines; they invite imagination, not dogmatism. I love the Church’s teaching on the communion of saints. I love the theology of the Trinity, which is not often preached because it is such a complex thing, yet it remains one of the most exciting discoveries of the nature of the divine.”

The question remains as to when O’Donohue actually left the priesthood. He himself later revealed to BBC broadcaster Michael Ford³, that he made the final decision alone on a mountain on New Year’s Eve 1999 and implemented it in November 2000. Since leaving parish ministry in the summer of 1995³, O’Donohue had held services³, family celebrations or funerals on and off. He stopped doing that too after 2000 and no longer appeared publicly as a priest.

He went his way in the church as long as he could. He never protested loudly against abuses in the church. Rather, he did it his own way until the pressure from the church leadership became too much for him. He later explained that he left rather quietly because he did not want to make life unnecessarily difficult for his priest friends and colleagues with a riotous or attention-grabbing farewell. Probably for this reason, his voice against sexual abuse and paedophile priests remained quiet. He knew that these crimes by fellow ministers would destroy people’s trust in the church as a place of refuge and that they would also drag the many blameless, good and kind priests down with them. Only in his later years would O’Donohue become more vocal and emphatically critical of the Church.

John O’Donohue left his sanctuary church, stepping over the threshold into the wilderness of civil life without deregistering from the church and without applying for a return to the laity. For the bishop in Galway, his old employer, canon law was therefore clear: John had resigned as a priest from active ministry in July 1995, thus retiring after 14 years of service. But he has always remained a priest according to the canon law of the Church. John was a priest until his death in 2008 – and thus, from the Church’s point of view, also committed to celibacy. Martin Whelan, the secretary of the Bishop of Galway sent me the following statement:

“I can also tell you that John O’Donohue never applied for laicisation. Therefore, from a canonical perspective, John O’Donohue was a priest, even though he was not engaged in active ministry. This would have prevented John from marrying within the Catholic Church, and any marriage he might have entered into, be it civil or religious, would not have been recognised by the Church.”

Once a priest, always a priest: John would probably have agreed to this postulate out of deep conviction, but for completely different reasons than the Vatican and the bishops. In the film documentary A Celtic Pilgrimage, released posthumously a year after his death, John said he had been a priest for 19 years and was now no longer in public priestly ministry. However, he saw priesthood as a matter of the heart, which was at best a prerequisite for church ministry: everyone was a priest, in their own way and in their own life, O’Donohue said.

Many fellow priests who did not share John O’Donohue’s way or all of his views nevertheless remained attached to him for the rest of his life. A participant in John’s funeral, Eoin O Suilleabhain, reported in the Irish Times about the funeral service on 12 January 2008 in Fanore. According to the report, nearly 40 ministers crowded the chancel, including two current and one former bishop. Diane Covington attended the memorial service at Galway Cathedral in February 2008 and described her memories to me: “Usually one priest comes out and genuflects, then leads the mass. In this case, they came out two by two, 20 of them and then the last one, which must have been his friend, led the mass. His first words were, ‘John O’Donohue was a holy man’.”

Nothing is more successful than success

Ten years earlier: On 9 September 1997, John O’Donohue’s book for which he had risked so much and then worked so hard was published: Anam Cara. The Book of Celtic Wisdom. Sales started cautiously, but then this book, which was difficult to classify in the border area of religion, spirituality and philosophy, stormed the bestseller lists in numerous countries, to the surprise of the publishing world.

The author himself was among those surprised, for he had not even dreamed of such a success. In Germany, the work of the still unknown Irish author was offered to the publishing house dtv. The dtv editor at the time, Bettina Lemke, now a successful author and translator herself, remembers: “I read the manuscript and knew immediately: We have to publish this. A truly profound and good book.”

Anam Cara became a long-running world bestseller, printed (and still being printed) in numerous languages and many editions. It freed O’Donohue from all material worries and catapulted him onto the stage of international prominence. His years as an assistant parish priest in the Diocese of Galway were definitely over. He was now a writer and soon a charismatic speaker, an impressive retreat leader and a spiritual beacon in rough times.

- Click here for the overview: All articles about the life and work of John O’Donohue.

- Click here for the book list: The books of John O’Donohue.

- Copyright: © Markus Bäuchle 2021. All rights reserved.

You can support our work with a donation

Photo credits:

2nd and 3rd photo from top courtesy of H.R. Hebeisen; 3rd photo from bottom courtesy of Pip Wilson; 2nd photo from bottom: dtv; photo at the bottom courtesy of Andy Espin. Andy lives and works as a photographer in England. Cover photo Connemara: Markus Bäuchle

Remarks:

1 Hans-Ruedi Hebeisen is the founder and head of HRH Fishing Hebeisen, a specialist shop and tour operator for fishing and angling supplies in Zurich. HRH and his wife Heidi founded a salmon fishing school in Connemara and have been organising fishing trips for decades. They still spend a lot of time in Ireland every year. Thank you, HR Hebeisen for the kind permission to use the photos.

2 Excerpts from an interview in Interview in The Sun Magazine, April 2007, by Diane Covington-Carter. More about and by journalist Diane Covington can be found on her website here.

3 Michael Ford describes this in his book “Spiritual Masters For All Seasons”, HiddenSpring 2009, a book worth reading, which John O’Donohue’s life partner Kristine Fleck thankfully pointed me to.

4 Father Kevin Hegarty knew John from their days studying together in Maynooth. Thanks to him for allowing me to quote from his very readable and extremely knowledgeable articles on O’Donohue.

This story / page is available in:

![]() German

German

bravo…a saint for sure, recognized by those that matter.

A holy man. One day he will be recognised as a saint.